Metabolism determines how genes function - new study says

Max Planck scientists collaborate in international research team on gene expression epistasis

You are what you eat, is an old saying, in its original meaning more referring to social status rather than the chemical processes in your body. A new study published by an international team of researchers, led by Markus Ralser at the University of Cambridge and the Francis Crick Institute, is revealing that this popular expression holds true down to the molecular layers in microbes.

It is known that the genetic make-up of a cell and its environmental context jointly determine the phenotype of a cell. In other words, knowing the genome, or DNA sequence, of an organism is telling a substantial proportion about how a particular organism will look alike, and how its genes function. But not everything is written in the genes. One player that is increasingly getting attention is the metabolic network - the compendium of biochemical metabolic reactions that occur in an organism. These reactions mainly depend on the nutrients (sugars, amino acids (proteins), lipids/fatty acids and vitamins) a cell has available as nutrient.

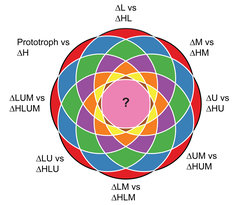

A collaborative research team involving the University of Cambridge, the Francis Crick Institute in London, the Max Planck Institute for Molecular Genetics in Berlin, the ETH in Zurich and the European Molecular Biology laboratory in Heidelberg and Hinxton, now systematically addressed the role of metabolism in the most basic functionality of a cell. The researchers took yeast cells, which are ideal research model organisms for large and systematic experiments and interrupted essential metabolic pathways required for the production of amino acids or RNA components (histidine, leucine, uracil, and methionine) in all possible combinations. Then they analyzed on all molecular levels how these cells respond when they consume rather than produce these molecules.

"We found almost 90% of genes, proteins or metabolites to be affected", says Tauqeer Alam, the first author of the study. "The effects were so strong, that a cell with different metabolic activity could respond to the same genetic defect in a completely different manner".

Researchers call it epistasis, when two genes acting in concert have a different effect as when they act alone. The researchers found that such interactions are the rule and not the exception, if a cell has metabolic defects. For instance, multiple metabolic defects are found in tumor cells that acquire multiple genetic mutations during their tumor development. The study thus helps to understand how biological properties change when cell’s metabolism is affected.

"This study brilliantly exemplifies how the combination of new omics technologies, like next generation sequencing and mass spectrometry-based proteomics and metabolomics, can be combined to dissect biological properties, that are not to be understood if you just look at part of the picture", says Bernd Timmermann, head of the Max Planck Society’s Sequencing Core Facility in Berlin.

"Another important aspect of our findings is a practical one for scientists", says Markus Ralser, the lead author of the work. "Biological experiments are often not reproducible between laboratories. We often blame sloppy researchers for that. It appears however, that small metabolic differences can exactly do that as well. We need to establish new laboratory procedures that control better for differences in metabolism. This will help us to design better and more reliable experiments."