What’s important?

Formation of the 3D structure and specific interaction between genes and enhancers represent independent layers of gene regulation

Based on insights from studying basic mechanisms of gene regulation and human hereditary diseases, it was previously assumed that the three-dimensional structure of DNA is essential for gene regulation. A team at the Max Planck Institute for Molecular Genetics led by Daniel Ibrahim and Stefan Mundlos specifically analyzed this effect by removing and repositioning binding sites for the transcription factor CTCF, a main driver of 3D chromatin folding. Upon removal of CTCF binding sites they noticed reduced precision, but no major changes in gene expression. Gene misexpression, however, was induced by redirecting regulatory activity through inversions or repositioning of CTCF binding sites. In the current issue of Nature Genetics, the scientists come to the conclusion that two independent layers of gene regulation exist, the spatial arrangement of genes by chromatin folding and an inherent specificity between enhancer and their target gene.

Shift of gene expression due to inversion of large genome segments

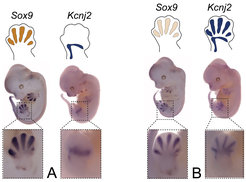

In these mouse embryos, a specific probe was used to label all cells, in which the genes Sox9 and Kcnj2 were active at the time of the study (whole-mount in situ hybridization). A shows the typical distribution patterns for the genes Sox9 and Kcnj2 in healthy embryos. B: In these embryos, a large DNA segment was inverted, which included the TAD boundary and Sox9 enhancers. As a result, the Kcnj2 gene shows a distribution pattern typical for Sox9, whereas Sox9 activity is slightly reduced.

Inside the nucleus the DNA strands of mammals including humans are organized into three-dimensional units called Topologically Associating Domains (TADs). Among others, the protein CTCF is responsible for the formation and maintenance of the TADs. CTCF binds to specific binding sites within the DNA and thereby induces the formation of loops and TADs. A TAD usually contains one or more genes and their regulatory elements called enhancers. Enhancers function as “switches” in the genome to control the activity ("expression") of their target gene.

In the last years, scientists at the Max Planck Institute for Molecular Genetics (MPIMG) in Berlin led by Daniel Ibrahim and Stefan Mundlos have analyzed the effects of disease-causing mutations on the formation of TADs. They were able to show that, due to the spatial arrangement of the TADs, enhancers come into close proximity to the genes they regulate. The researchers therefore assumed that the correct formation of a TAD was critical for gene regulation. This interpretation was supported by studies of duplications and deletions of large genome segments of various sizes, which led to malformations and congenital diseases in humans. The duplications caused the formation of new TADs, in which genes from one TAD were combined with the enhancers of another, whereas deletions resulted in the fusion of TADs. As a result of the rearrangement, genes were now regulated by enhancers that previously belonged to another gene ultimately leading to gene misexpression and disease.

Systematic analysis to investigate the effects of genomic rearrangements

However, recent findings from other research groups suggested that the structure of TADs may not be as crucial for gene regulation as previously thought. To address this apparent contradiction, Ibrahim, Mundlos and their colleagues carried out a systematic analysis in mice to study the function of TADs, and in particular the factor CTCF, in more detail. The researchers focused on the well-studied Sox9 region, where two large TADs are located, one containing the Sox9 gene and its enhancers, the other the gene Kcnj2 and its enhancer. The boundary between the TADs consists of four CTCF binding sites, but further binding sites are located within the Sox9 TAD and the Kcnj2 TAD. In a series of experiments, the researchers first depleted the binding sites at the boundary. They found that the overall 3D configuration of the region stayed intact even without CTCF binding at the boundaries. Only after additional deletion of all CTCF binding sites within the TADs, the structure of the Sox9 region got lost and the two TADs fused to one big TAD. "We were able to demonstrate that size and structure of a TAD are not defined by the boundary only," Ibrahim explains. "Like with most things in biology, it is not only one factor that makes or breaks the system. Instead, we are dealing with a buffered system to ensure that single mistakes, such as mutations, do not result in a complete loss of function." Surprisingly, loss of the TAD boundary and even of the 3D structure did not lead to comparable changes in gene expression. The scientists noticed a reduced precision in genes activation, but no major changes in gene expression compared to normal development.

But if the loss of CTCF leads to a fusion of TADs, similar to the effect observed in the deletions, why do we see gene misexpression in one and not the other? To further investigate the effects of genomic rearrangements on TAD formation and gene expression, Ibrahim and Mundlos designed a series of experiments, in which they cut out sections of DNA of different sizes and put them back in opposite direction (inversions). This repositioned the CTCF binding sites at the boundaries and changed their orientation, leading to massive effects on TAD formation and gene expression. Redirecting CTCF with the inversions led to an activation of the neighboring Kcnj2 gene by Sox9 enhancers and a disease phenotype. Repositioning of the boundary led to insulation of Sox9 from its enhancers and thus a Sox9 loss in expression.

Due to a systematic design of their experiments, the team led by Ibrahim and Mundlos was able to clearly distinguish the different functions of the CTCF binding sites at the boundary and within the TAD. An intact TAD boundary has always been able to separate individual functional areas from each other. Within the TADs, however, different structural changes also led to different effects on the interaction of enhancers and genes. "In fact, the specificity of the enhancers for their target genes is significantly higher than previously thought," says Mundlos. "If their position in the genome remains unchanged, enhancers appear to mainly address “their genes”, even without their interaction hub being defined by a TAD. Only conditions interfering with normal enhancer-gene interaction, for example, inversions that redirect TAD substructure and enhancer and connect enhancer activity to new target genes will lead to misexpression."

Independent layers of gene regulation

The findings of the Berlin team support the idea that spatial separation into TADs and specific interaction between enhancer and gene represent two independent layers of gene regulation. They stabilize each other but are not inherently linked. Furthermore, the results explain the alleged discrepancy that removal of CTCF or its binding sites has little effect on gene regulation, whereas structural variants caused by hereditary diseases can result in dramatic changes of gene regulation. "This also highlights the need for systematic analyses and different types of experiments in basic research," Ibrahim says. "With the results of the individual experiments, we could have written two papers with contrasting conclusions. It was only by bringing together the results and conducting additional studies that we were able to understand what these conflicting outcomes mean. "

Implications for the interpretation of disease-causing mutations in humans

The findings have direct implications for the identification and interpretation of disease-causing mutations in humans. "Based on these results, we can better predict, which mutations have the potential to disrupt TADs and cause disease," explains Mundlos, who, in addition to his work at the MPIMG, also heads the Institute of Medical Genetics and Human Genetics at Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin. "Most rearrangements that we see in patients do not act by removing small parts of the genome. Much more important are large shifts of DNA segments leading to active reorganization of the 3D structure and disruption of physiological gene-enhancer interaction.”