Three generations in the lab

Student internship at the Institute

How do you become a scientist? How do researchers work and think? Highschool student Lioba wanted to find out and approached our independent group leader Tugce Aktas for an internship. She spent two weeks in the lab, observing the work of PhD student Lisa Martina, talking to other labs and trying things out for herself. We paid her a visit and talked about her experiences.

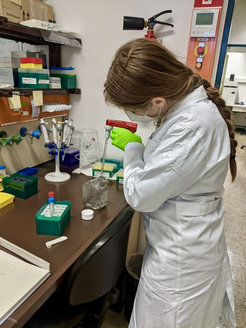

We meet at the Institute’s tower 4 with its rustic charm of the eighties: brown ceramic benches, sand-colored flooring, olive doors. As with all the labs, the rooms are crammed with equipment. Bottles with blue lids and stacks of consumables sit on the shelves. In the midst of it all is Lioba, a 14-year-old student intern from the John F. Kennedy School, with her hair braided tightly and wearing a green plaid shirt under her lab coat.

“I've probably learned more about science in the last week than I have in class in the last few years,” she says. “It's great fun, I really like it a lot.”

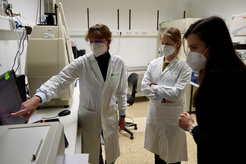

Next to her is PhD student Lisa Martina, sporting a pair of hexagonal glasses with gold rims. The Italian studied in Oslo and Berlin and started at the Institute only three months ago. At the moment, we are in the middle of the omicron wave, which is why the lower halves of all faces disappear behind FFP2 masks.

“I didn't think it would be so difficult to explain our work in simple terms,” Lisa says, laughing. “I couldn't remember what I knew when I was her age, and our work is actually pretty complicated. So I had to pinpoint the most important aspects for her. But Lioba understands very quickly, so it's not really a problem.”

Having met early, group leader Tugce Aktas is missing from our group and we shuffle around in the laboratories, between humming refrigerators, centrifuges, incubators and the occasional microscope.

Becoming a good mentor

This is where the two women are working side by side, every day for two four-hour sessions. For the graduate student, this involves a fair amount of planning. Lioba specifically asked not to be assigned a project of her own, but to observe the “real work” and witness when new results materialize.

The time that Lisa invests in supervision already payed off emotionally, she says, pointing to the microscope behind her: “I was counting cells in cell culture here the other day, as I had done dozens of times before. When I let Lioba take a look, she suddenly said, 'So that's what we're made of!' and I suddenly realized why I love my work so much.”

She had never mentored anyone in this way before. Being in her mid-twenties, she has only recently graduated from university herself – the stage of life that her protégé is preparing for in the coming years.

Hands-on science

As in many biological laboratories, the people of the Aktas lab mostly handle colorless liquids in minute volumes. Usually, the research subjects are not visible to the naked eye. Isn't this a little dull for a teenager?

“I first had to learn how small a microliter is – it's such a tiny droplet,” Lioba says. “But this is actually what fascinates me. I also like astronomy, because you study things that are unknown and can't be seen just like that.”

Lioba did a Western blot during her first week. She counted cells at the microscope and harvested the correct volume. She learned to handle pipettes and calculate dilution steps. This was followed by meticulous application to a protein gel for SDS-PAGE and the transfer process to a blot membrane, incubation with antibodies, and detection of the light signals in a camera box – a process that took several days.

“Who would have thought that experiments would be so lengthy?,” Lioba says. But this didn’t take away from the experience: “I didn't think much of biology at all when I arrived at the institute. It's actually more interesting than I thought.”

Being a role model for the next generation

Meanwhile, Tugce Aktas has finished her meeting and joins us. As a group leader, the safety of her staff is a priority. Wouldn't it be better to talk in a conference room? Wouldn't we have more space there? We agree and hurry through the corridors, moving into one of the seminar rooms in tower 3 to continue our conversation.

Lioba has noticed how many women work at the Institute. “Of course, I didn't expect there to be only men in science. But I was surprised how many women work here. It actually made me very happy. In the news and in history, it's always just guys doing stuff.”

This is a nice compliment, but the Institute did not yet achieve gender parity, although it tries pretty hard. As elsewhere, the lower-paid positions are filled largely by women. Among students, women still outnumber men, but as researchers move up their career, the ratio eventually tips, perhaps at the level of postdocs and group leader positions. The ranks of directors are all men – and have been since the Institute was founded in the 1960s.

“I feel it's my duty to be a role model and show girls that they can make it in science – that's why I've only ever accepted girls and women for internships,” says the group leader. “ I think that a lot has changed for the better in recent years, but it simply takes time for such a cultural change.”

Get a taste and make an informed decision

“Everyone should explore and gain experience in their future role so that they can make an informed decision on whether they really want to take the plunge,” Tugce says. “I'm not just talking about the interns, but also my doctoral students, who have to figure out what their future looks like after they finish their PhDs.”

Tugce sees herself in Lioba and is reminded of her own youth: “I had my first lab experience when I was 15 years old. From then on, I knew I wanted to spend the rest of my life in the lab. I have since moved up from a lab worker to a management position and have mentoring and management responsibilities. I delegate a lot and have to deal with manuscripts and editors.”

Making the world a better place through curiosity

The three women's occupations differ enormously. Yet only about a decade of life experience separates them each. What unites them is their enthusiasm for mathematics – Tugce and Lioba both competed in math Olympiads – and the mysteries of nature and the drive to get to the bottom of them. This makes them part of a special group in the population that is actually quite at home in the basic science-oriented Max Planck Society.

“In university, I sometimes thought, what's wrong with me that I am so interested in biology for its own sake, not primarily because of a desire to improve the world,” says the doctoral student. “I used to have a very different, unrealistic image of why people do research.”

Doing science out of curiosity and making the world a better place are not mutually exclusive, the group leader replies. “You never know what a discovery might be good for. A few years ago, CRISPR/Cas9 was just an obscure bacterial defense mechanism that hardly anyone was interested in. Now it's revolutionizing research, and even clinical applications aren't far off.”

Are the researchers' revelations surprising to the student? “Not really, I've always thought that people in science mostly want to find things out.”

What schools cannot do

The three women agree that the school system does not convey the complexity and practice of science. “In school, we always asked ourselves, why do you need to learn this? What's the relevance? That's where the school system fails to inspire the next generation of researchers,” Tugce says. “Yet in biology, it's so easy to make these connections and relate them to your own life.”

“I didn't realize these intricate connections until after I graduated. Much too late, so even the university failed me,” the researcher says. “I think asking ‘Why?’ is very important. If you don't make those connections in your project, the progress will be very small. Discoveries are bigger and more significant when you see the context.”

“If we look at climate change and the complex systems on Earth that are affected by it, the population actually needs basic training in statistics, scientific thinking, and problem-solving strategies to deal with it in a reasonable way,” Lisa says. “I wish this was taught more in schools.”

Supporting schools

Internships can offer something that schools could never do. It is the first time Tugce has offered a student internship in Germany and was surprised by how much preparation and structure the school requires and how much effort they put into making sure their students are doing well. For example, Tugce received calls from teachers asking in detail about their student.

“It would be great to have a structured program for regularly mentoring pupils. Graduate students in their first year would be well suited for this task,” Tugce says. “Of course, it's not for everyone and you have to really want to do it; it depends a lot on the individual person. No one should be forced into it.”

Other labs at the Institute, such as the ones led by Stefan Mundlos, Marie-Laure Yaspo and Heiner Schrewe, regularly host interns. Schrewe also visits public schools to talk about his research activities. In addition, the Mundlos Lab has hosted multiple week-long internships for larger groups of students of the Schadow-Gymnasium.

Future plans

The first week of the internship is now behind Lioba. Can she imagine becoming a scientist at this point? "Honestly, I have no idea at all what I want to do professionally when I grow up," she answers, a smile glinting from beneath her mask. "I definitely like biology more than I did before the internship, but I just can't tell."

"We have to do our part. We have to show the next generation what research is like and be a role model," Tugce says. "If young people take back to their classes what they have experienced here, we can really make a difference."

The researchers return to their lab. This afternoon, Lioba and Lisa will finish the immunoprecipitation they prepared a few days ago. Soon the internship will be over and Lioba will hopefully return to her school with many impressions to tell her classmates.

![[2025] - Co-evolution of transposable element activity and host genome](/4571553/teaser-1666694817.jpg?t=eyJ3aWR0aCI6MzYwLCJoZWlnaHQiOjI0MCwiZml0IjoiY3JvcCIsImZpbGVfZXh0ZW5zaW9uIjoianBnIiwib2JqX2lkIjo0NTcxNTUzfQ%3D%3D--791f1b42061e2ab65f2361b8c718d5336a66855a)